Romania’s 2025 Presidential Elections: Who Gets to Decide What Romania Stands For?

Author: Ioana Brunet

Cover picture: Inquam Photos/Malina Norocea, Sabin Cirstoveanu (Romania-Insider.com)

With a few days left until the final round of Romania’s presidential elections, the country faces a deeply important and polarizing choice.

For the first time in the post-socialist Romanian history, neither of the traditional parties – the Social Democratic Party (PSD) nor the National Liberal Party (PNL) – have a candidate in the run-off. This alone marks a seismic shift in Romanian politics, reflecting widespread public disillusionment with the established parties, especially after last December’s annulled elections, which were tainted by allegations of Russian interference (a more detailed explanation here).

Now, the choice lies between two self-proclaimed anti-system figures: George Simion – the leader of the far-right Alliance for the Unity of Romanians (AUR), and Nicușor Dan, the independent mayor of Bucharest and a former civic activist. Both are populist in rhetoric – using the “us versus them” dichotomy as much as they can, both are critical of the political elite and eager to promise reform, both are on the right side of the political spectrum (Simion on the extreme, Dan on the center-right). Yet, their visions for Romania diverge profoundly and become especially visible in the pro-EU – anti-EU debate.

George Simion, who secured 40% of the votes in the first round on May 4, 2025, has built his campaign on nationalist, “anti-globalist”, sovereignty tropes. He is openly critical of the European Union, supports ending aid to Ukraine and has echoed narratives commonly found in Russian propaganda (Ukraine is an invented state, the war there is a war between Christian Orthodox believers, and it is better to have an unjust peace that to let the conflict escalate). This is part of the reason why he is banned from entering the neighboring Ukraine and Republic of Moldova, along with suspicions of past meetings with Russian agents on the territory of these countries. He has also publicly aligned himself with Donald Trump and the “Make Europe Great Again” (MEGA) movement, raising concerns regarding Romania’s future geopolitical orientation, away from Europe and closer to Russia.

Domestically, Simion has a history of aggressive behavior, including bursts of anger and bullying language in Parliament. He started gaining public attention in 2012, as an ultranationalist agitator and far-right football hooligan, asking for the reincorporation of the territories lost by Romania after the Second World War, like Bessarabia and North Bukovina. In 2019 he founded the AUR Party and in 2020 he capitalized on the crisis brought by the pandemic, securing the support of the people distrustful of the vaccine and the EU policies of the time. His confrontational style has drawn both criticism and admiration. For most of his supporters, many of them from the Romania diaspora (60% of whom voted for him in the first round), Simion represents a long-awaited voice for dignity, sovereignty, national pride and criticism of EU policies: “I am representing change and have never been in power”, he declared for the Financial Times. On the other side, for his critics, his temperament, vague policy proposals, admiration for authoritarian models (such as that of Viktor Orban’s) – all this raise alarms about the risk of democratic backsliding. Ironically, during this campaign, Simion downplayed his nationalism and appealed to the Hungarian minority in Romania and to Viktor Orban, hoping to gain their support. After a first positive reaction, a few days later Orban distanced himself from Simion stating that he does “not support any form of political isolation against Romania and its leaders” (source: Euronews).

On the other side, his opponent is Nicușor Dan, a Sorbonne educated mathematician turned reformer, who was recently elected for the second time as mayor of Bucharest. He rose to prominence for his battles against corrupt real estate interests in the capital and his technocratic, albeit distant and introvert, political style. Dan is unwavering in his pro-EU and pro-Ukraine stance and has been campaigning on a platform of transparency, urban development and rule of law.

However, Dan is not without his own controversies. Critics accuse him of being uncommunicative, overly detail-oriented to the point of micromanagement and at times hypocritical – allegedly granting building permits at will, or for his personal gain, while publicly opposing real estate corruption. Moreover, his conservative views on LGBTQ+ rights, which led him to leave the progressive USR (Save Romania Union) Party, have drawn criticism in the past from liberal circles.

What makes these elections exceptional is the context, more than the candidates. After decades of democratic development and a steady, albeit fraught, trajectory towards European integration – which was seen as default, Romania is now grappling with a crisis of political meaning and national identity. Economic hardship is bound to come; everybody agrees on that. Austerity measures are likely to be implemented, after years of fiscal mismanagement and not properly accessed or used European developmental funds. Class driven, as Costi Rogozanu and Bogdan Iancu argue, the public polarization is based on a Manichean understanding of the electorate, like educated versus uneducated people, good versus bad European citizens, democracy versus autocracy, urgently calling for side picking and leaving little room for dialogue.

Both sides speak in terms of “salvation”. Simion’s supporters are hopeful of gaining back their dignity, reclaiming national control and ending the humiliation of economic emigration. Dan’s camp sees this vote as an existential battle for the survival of democracy, an urgent need to resist the tides of extremism, nationalism and potential authoritarianism.

More than a contest between two presidential candidates, these elections represent a referendum on Romania’s path: toward Europe or away from it. The outcome will have significant implications not only for Romania’s domestic policies, but also for its role in the broader European context.

From a more personal perspective, as a researcher dealing with memory and populism in Bukovina, the current situation is both information-rich and overwhelming. While conducting fieldwork in a small Romanian town during the early days of the presidential campaign in April 2025, what initially caught my attention was the striking visual dominance of AUR posters in the public space, especially in contrast to the near-complete absence of promotional materials for the other ten candidates.

Even at that stage, when the public had not yet polarized around the final two contenders, initiating dialogue proved difficult. People often declined interviews even those that only lightly touched on political topics. For many, practicality outweighed political allegiance. For example, a person told me that he had received a good black hoodie marked with the AUR distinctive yellow branding and he just covered the logo with black permanent marker: “It would have been a shame to throw it away”. A sense of silence hangs over the town, mirrored by low voter turnout – less than 50%.

In contrast, the noise on social media is hard to follow. Since leaving the field, I have been monitoring public discourse and online reactions. Issues of class, money, minority rights, identity, education, religion are all weaponized by both sides. What emerges is a dialogue of the deaf – each side mocking and vilifying the other, constructing the “Other” as an existential threat. History and memory – raging from medieval rulers to interwar fascism, the socialist era and the post-socialist years – are invoked and instrumentalized to legitimize competing political stances. The result is a cacophony that often drowns out meaning and uses memory only as a political tool.

Navigating this terrain has been and still is emotionally taxing. I find myself left with more questions than answers to this situation. One of the most pressing is how to reconcile a genuine desire to hear all perspectives with the urgent need to resist and block extremist views. Where does engagement end and self-protection begin? How will this polarization shape the next stages of my fieldwork? And what impact will it have on an already fragmentated community?

I am aware that these questions have no immediate answers; only time will reveal the outcomes. Still, the results of the vote on Sunday, May 18, 2025, will undoubtedly mark an important moment –from a personal to a geopolitical level.

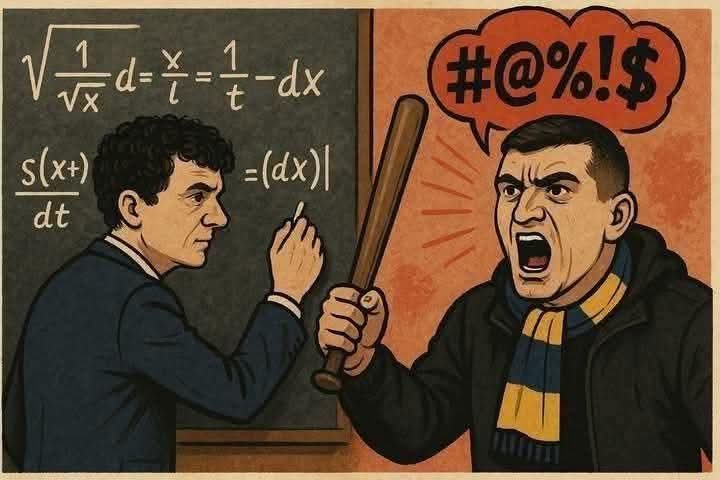

Social media meme (AI generated, author unknown): the educated Dan vs the aggressive Simion

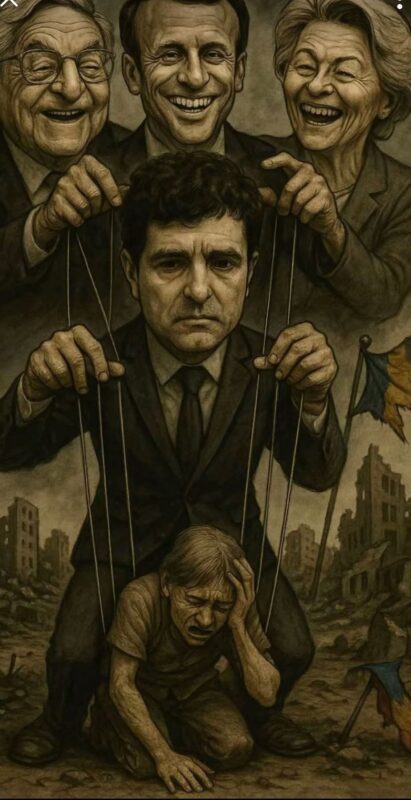

Social media meme (AI generated, author unknown): Nicusor Dan being portrayed as the puppet of the European Union and George Soros.